First, the crisis will not end, for many years. The “fear” of the virus coming back will keep us in lockup—or as Newsom calls it “lockdown”, for many years. Schools will not totally open for years, for fear of the virus and the large number of people refusing to take the vaccine among health professionals. If they won’t take the vaccine why would you?

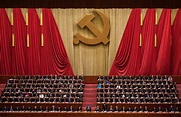

Masks, curfews and controlling the number of people allowed to gather will kill off professional sports, entertainment, concerts and movies. Hollywood, the promoters of a fascist, totalitarian government will be killed off.

No problem, they will move to Canada, Georgia, Texas and Florida to make movies. Hollywood has been killed by a drive by murder—Newsom and the Democrats are the culprits. Hollywood folks will go to Free States, with low taxes, cops that are allowed to do their job and schools that teach not indoctrinate.

When The Crises End, Will L.A. Still Be The Movie Capital? Maybe Not.

By Michael Cieply, Deadline, 1/7/21

When this is all over—Covid, unrest, financial reconstruction—will Los Angeles still be the Movie Capital? Perhaps not.

This week, the Federal Emergency Management Agency put Los Angeles County at the top of its new National Risk Index, which calculates danger from natural disasters like earthquakes, fire and flood. It was only the latest in a string of threats that have movie people, and everyone else here, wondering if California has seen its golden hour come and go.

You can’t get into a hospital, and orders are to conserve oxygen. For the moment, Los Angeles is at the center of the pandemic.

On the policy front, there’s only more trouble. Facing fiscal collapse and a rising tide of homelessness, legislators have been floating proposals to boost a top tax rate of 13.3 percent, already the nation’s highest, to something like 16.8 percent, or to impose an annual wealth tax that for ten years would follow anyone unwise enough to have spent 60 days in the state. A nine-week film shoot could saddle a wealthy director, producer or star from New York, London or Seoul with a California assessment on his or her worldwide assets for a decade.

Given all that, it’s no surprise that the financial and tech elite, following a worrisome chunk of the middle class–U-Haul just ranked California dead last in its annual inflow/outflow survey–have already decamped. Elon Musk, Charles Schwab and Oracle are off to Texas.

Which raises an inevitable question: Can the film industry, when it sputters to back to life, be far behind?

L.A.’s movie capital status—its pop cultural hegemony, what we like to call “Hollywood”—dates vaguely to the 1920s. In the early years, New York-based film companies kept a tight hold on production satellites that found the weather, light and acreage in Southern California congenial. But studio chiefs and a growing movie community quickly slipped the East Coast leash.

In a sense, the founding of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences in 1927 was a declaration of not just independence, but imperium. Wall Street might control finances. But the screen universe, the creative part, would be governed from here.

Over the years, Hollywood weathered challenges to its capital status. In the early 1960s, a vogue for European cinema left observers like Christopher Rand of The New Yorker convinced that Los Angeles, then a swamp full of bad television, had ceded movie primacy to London or Paris. But counter-cultural film, and then the blockbuster era, brought things back home.

Later, government subsidies in Canada, New Zealand, Michigan, Louisiana, New York, wherever, scattered production and post-production workers to the winds. Yet California fought back with subsidies of its own, as many of those competitors exhausted their funds. And, somehow, the weight of studio real estate, plus a vast distribution and marketing apparatus and the enduring power of myth conspired to keep the film world anchored in a rough triangle that reaches from Malibu to Culver City to Burbank.

But even before Covid-19, the glamour capital was being hollowed out by forces more threatening than runaway production. Dozens of companies were swept away in the post-2008 financial collapse. Many, perhaps most, of the highest earning stars quietly based elsewhere as California pushed its so-called “millionaire’s tax” above 13 percent. Internally, a crisis of confidence meanwhile transformed the film Academy, as it responded to claims of racial and gender bias by flooding the membership rolls with stars and filmmakers from around the world. The net effect was a rapid internationalization that last year helped to deliver a Korean-language Best Picture, Parasite, from a small, New York-based distributor, Neon.

As Bong Joon Ho stepped up to collect his various Oscars, Los Angeles felt a little less like the center of the movie world. Gone were the days when you could package a winning film around the pool in Brentwood or on a deck in the Colony. (Before going to jail, even Harvey Weinstein, that roving collector of films from abroad, had sold one of his companies to the Burbank-based Walt Disney Company, and was careful to spend half his time both managing and abusing its successor right here in L.A.)

At this point, it wouldn’t take much to change Los Angeles from movie capital to movie outpost. Given the drag on vaccine distribution and persistence of the virus here, production elsewhere is likely to get a head start. Worse, if one big company—Disney, with its affiliated remnants of Fox—were to move its flag to Florida, the books would close on an era.

Unlikely?

The Rose Bowl went to Texas. The Oscars are still hiding from the latest viral surge. (And never mind that perennially delayed museum.)

After a year like the last, anything is possible.