Newsom, thanks to COVID money had a $97 billion surplus last year. Today, after he blew all that money and more, we have a $73 billion deficit. The State colleges and universities are in the same boat—and he is on the governing bodies of both the UC and State college systems.

“Suddenly, colleges and universities were scrambling to spend the money as quickly as possible, despite limited or inconsistent federal and state guidance. Experts worried the relief money was too much, too fast. Campuses failed to take full advantage of the money, according to a 2021 state audit, and they made decisions that “prioritized students differently.”

Now, as the final deadline to spend the money approaches this June, the boom is turning to bust. Most schools have exhausted the money, often through major purchases, such as new laptops or tuition waivers for students. But maintaining those programs can be costly, and with the state facing a budget deficit this year, colleges say it’s not clear where the money will come from next.”

On the other hand, do we want to spend more money on campuses and classrooms that have turned into Nazi training grounds?

California colleges got billions in pandemic relief funds. What will happen once it’s gone?

BY ADAM ECHELMAN, CalMatters, 5/1/24 https://calmatters.org/education/higher-education/2024/05/pandemic-relief-funds/

IN SUMMARY

Congress gave California’s public colleges and universities more than $8 billion in emergency funding during the COVID-19 pandemic. Now the money is drying up and schools are faced with a grim financial future.

In March 2020, colleges were on the verge of a crisis. Students were dropping out en masse, and California’s public colleges and universities predicted they might lose billions of dollars within the year.

Enter the federal government. In three installments over the following year, Congress gave more than $8 billion to California’s public colleges and universities as part of a national rescue plan. For the California State University system, the stimulus money accounted for roughly a quarter of its annual revenue.

Suddenly, colleges and universities were scrambling to spend the money as quickly as possible, despite limited or inconsistent federal and state guidance. Experts worried the relief money was too much, too fast. Campuses failed to take full advantage of the money, according to a 2021 state audit, and they made decisions that “prioritized students differently.”

Now, as the final deadline to spend the money approaches this June, the boom is turning to bust. Most schools have exhausted the money, often through major purchases, such as new laptops or tuition waivers for students. But maintaining those programs can be costly, and with the state facing a budget deficit this year, colleges say it’s not clear where the money will come from next.

For students, the boom was especially short-lived. Over three years, California’s colleges used the federal money to give cash to students, typically less than $1,000 each. For many struggling students, it wasn’t enough.

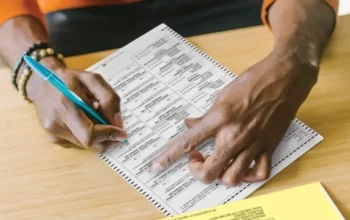

How pandemic relief funds ended up in students’ hands

After graduating high school in 2020, Jose Castillo enrolled at Merced College, but he didn’t stay long. He needed money. Like many students his age, he dropped out in fall 2020 and started working 12-hour shifts, five days a week, at a food packaging warehouse. As long as he took a few overtime shifts, he could make nearly $2,000 a month.

He eventually quit and re-enrolled at the community college, where he’s studying animal science. Along with his regular financial aid award, about $10,000 a year, his college gave him an additional $2,000 over two semesters as part of the pandemic relief money. “I’m thankful for whatever I get,” he said.

Castillo lives with his parents and younger brother on a dairy farm, about a half hour from the college. While he isn’t working anymore, his parents work 12-hour shifts at the farm. To help, he drives his brother to school and pays for gas. He also pitches in on groceries.

Covering family expenses, school fees and textbook costs, the money “just goes away,” he said. “Right away.”

Of the $8 billion in federal aid, colleges were required to give about half directly to students. The money went to the poorest students, who often spent it on daily necessities, such as housing, food and transportation, according to federal reports.

But the criteria varied: the same student could qualify for COVID relief money at one school but not another. At Chico State and UC San Diego, for example, students applied for aid by submitting a simple form that only asked the amount of money they needed. Students at other schools, such as Cal State Long Beach State and Sonoma State, needed to write explanations justifying their need and some were denied, according to the 2021 state audit.

The other half of the $8 billion went to “institutional” needs, which colleges could define broadly, such as equipment or staff training. Compared to other federal relief, such as the Payment Protection Program for business loans, the higher education relief program had low levels of fraud, said Kevin Cook, who helps lead the higher education center at the Public Policy Institute of California. In 2022, the Institute released a report on how California’s public colleges and universities used pandemic relief money.

“It seems like these colleges, when given extra funds, were spending it on areas that were needed,” Cook said. “They didn’t build a new football field. They spent it on things that would make the campus safer or help students stay enrolled.”

Missing out on millions

Still, the federal relief program was far from perfect. The federal government bypassed the state and issued stimulus money directly to colleges and universities, allowing schools to spend the money quickly but with relatively little oversight.

Congress gave more than $8 billion to California’s public colleges and universities as part of a national rescue plan.

In their reporting, schools often used vague terms to describe how, exactly, they spent the money they received for institutional use. UCLA reported putting the vast majority of institutional funds towards recuperating “lost revenue” from tuition and dorms when students stopped attending. The university declined to specify what they used that revenue for.

Many community colleges were equally vague, though not all. At Yuba College, an hour north of Sacramento, administrators decided to give students additional cash by using the money designated for institutional needs. Because of low vaccination rates across the county, they also gave out nearly $700,000 worth of Amazon gift cards as incentives for students to get vaccinated. In East San Jose, Evergreen Valley College put most of its institutional needs dollars toward new technology, tuition discounts and waivers for students who had accumulated fines and fees.

Often these expenses come with ongoing costs that the one-time federal funding can’t cover. At Evergreen Valley College, Vice President of Administrative Services Andrea Alexander has been scaling back how often departments get technology upgrades while searching for other funds to pay for future maintenance. She said the school will likely ask voters for a bond in the next five years to cover the ongoing cost of technology. The bond will also pay for cybersecurity upgrades, which are increasingly necessary as community colleges try to stem an onslaught of financial aid fraud.

Amid the flurry of federal funding, the audit found that many public colleges and universities had neglected to apply for grants they were likely eligible for. Following the audit’s recommendation, the UC system found nearly $74 million in expenses that colleges could bill to the Federal Emergency Management Agency, according to Stett Holbrook, a spokesperson for the president’s office. The same agency approved just over $3 million in reimbursements from the Cal State system, with nearly $20 million in expenses still pending review.

A spokesperson for the California Community Colleges Chancellor’s Office, Paul Feist, said it has not issued any formal guidance to schools about requesting such reimbursements and that it “does not monitor what claims, if any, districts made to FEMA.”

‘I wouldn’t say it lasted long’

On a per-student basis, community colleges received less money than UC or CSU campuses, even though community colleges educate the majority of low-income students in the state. That’s because the federal government initially prioritized giving money to schools with a higher percentage of full-time students and to schools that had more Pell Grant recipients.

Federal Pell Grants go directly to low-income students. Though many community college students qualify, they rarely apply for the money or receive it. Community college students are also more likely to attend part-time, since many work.

“They didn’t build a new football field. They spent it on things that would make the campus safer or help students stay enrolled.”

KEVIN COOK, THE PUBLIC POLICY INSTITUTE OF CALIFORNIA

Initially, some community college students didn’t qualify for any aid. In January 2022, Mikala Hutchinson began taking classes at MiraCosta College in Oceanside, north of San Diego. She was taking high school-level classes since she didn’t have a high school degree or equivalent.

For decades, adult students without a high school degree or equivalent have been left out of the financial aid system, even when they qualify. When the federal government first announced the COVID-19 relief grants, it neglected to specify whether students like Hutchinson were eligible.

Since enrolling, Hutchinson said navigating financial aid has been “a massive headache.” It wasn’t until May 2022, when she was taking college-level classes, that she got any financial aid from MiraCosta College. Over the course of a year, she received just over $2,000 in COVID-relief funds, all of which she put towards child care.

Hutchinson has two young children. That year, she paid more than $20,000 in child care. The money “helped in the beginning for sure,” she said, “ but I wouldn’t say it lasted long.”