Some taxes, like a sales or property taxes, are direct. Others, like the cost of mandated programs or the killing of cheap electricity are called an “energy tax”.

“That’s the premise undergirding new research from the nonprofit Next 10 and UC Berkeley, which found that at least half of California’s electricity rates cover costs well beyond the direct price of supplying electricity to our homes — something researchers called an “energy tax.”

Instead, the study found, this tax, which accounts for half to two-thirds of residents’ electricity rates, is going toward covering the cost of a warming world. This includes climate adaptation measures like wildfire mitigation, maintaining transmission lines, hardening the grid against extreme weather events, and social programs to assist low-income residents.”

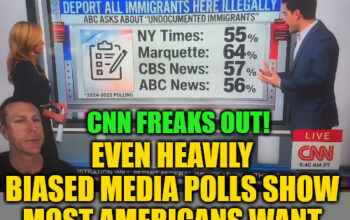

This is why California is in the top three most heavily taxed States category. Newsom is working hard to make it number one. Why? So, more people can move out, leaving room for his preferred resident, illegal aliens.

California’s high energy prices could cost the state its climate goals

By Jessica Wolfrom, SF Examiner, 9/22/22

California’s climate goals rely heavily on the rapid electrification of cars and buildings, but as the costs of electricity continue to climb, there’s growing concern that residents will be unwilling to make the switch.

That’s the premise undergirding new research from the nonprofit Next 10 and UC Berkeley, which found that at least half of California’s electricity rates cover costs well beyond the direct price of supplying electricity to our homes — something researchers called an “energy tax.”

Instead, the study found, this tax, which accounts for half to two-thirds of residents’ electricity rates, is going toward covering the cost of a warming world. This includes climate adaptation measures like wildfire mitigation, maintaining transmission lines, hardening the grid against extreme weather events, and social programs to assist low-income residents.

And while such programs are critical for the future, researchers argue if ratepayers are left footing the bill, it could have a chilling effect on people’s desire to make the all-electric switch — imperiling California’s climate goals.

“If you’re thinking about buying an EV or you’re thinking about putting in a heat pump, if electricity costs a fortune, then that disincentivizes you,” said Severin Borenstein, an energy economist at UC Berkeley and co-author of the new study.

Not only that, but as climate change accelerates the ferocity and duration of wildfires, heatwaves and drought, the price of electricity will continue to rise as utilities scramble to shore up infrastructure, further dissuading people from going all electric, said Borenstein.

The research comes at a moment when historic investments in climate action are coming from both state and federal government coffers. Earlier this month, California announced $54 billion funding for climate policies to slash pollution and hasten the state’s transition to clean energy.

The state moved to ban the sales of new gas-powered cars and light trucks by 2035. And on Thursday, the state’s air resources board voted to approve a plan that would prohibit the sale of natural gas heaters in commercial and residential buildings by 2030, inching the state closer to full-scale electrification.

The spending builds on the passage of the Biden administration’s Inflation Reduction Act, which set aside $370 billion toward climate action, with a sizable portion incentivizing the adoption of all-electric vehicles, appliances and buildings.

But these incentives will work only if the cost of that power is affordable, the new research points out.

“The report suggests that we have a real problem here,” said Borenstein. He said that even the installation of EV charging stations is being folded into the price of electricity. So while the government subsidizes the upfront cost of an electric car, paying to charge it could be prohibitive.

Moving around costs

But funding energy transition also represent a major opportunity to rethink how electricity prices are structured, said Borenstein. The report lays out two leading solutions to dramatically shift how the state funds electrification so that it’s not loaded onto ratepayers.

The first is to move some of those costs, especially public programs like wildfire mitigation, onto the state budget. “In many natural disasters, the state steps in and helps,” said Borenstein. “Except if it goes by an electric wire.” In that case, the utility is responsible, he said. “But what that really means … is that you can just add it into the bill.”

The second is an income-based charge or a rate reform requiring wealthier households to pay a higher monthly fee.

Though the researchers anticipate lawmakers and utilities will need to hash out the details and feasibility of these solutions, Borenstein said that if we don’t make substantive changes soon, those least able to shoulder the burden of these rising costs will be hit the hardest.

Low-income households in PG&E’s service area, for example, pay about 3% of their annual income toward this electricity tax, researchers found, which is more than three times the share of income for wealthier households. These effects are only magnified during moments when energy demand is highest, such as during this month’s blazing heatwave.

“There’s no question that if we don’t address this problem and continue down the road that we are currently on, electricity will just not be an affordable option,” said Borenstein. “The electricity will just cost too much — and not because it actually reflects the true cost. Because we’re paying for all sorts of other things through electricity prices.”