The legislature put Prop. 1 on the ballot. The purpose is to put into the State Constitution, the “right” to kill babies, without any punishment. Newsom and the Democrats, plus one Republican, want to make California the Killing Fields of the United States—rivaling Cambodia and its massacre of hundreds of thousands of citizens.

“Advocates of animal rights often equate sentience with consciousness, without distinguishing how consciousness is to be understood.

“Sentience” (from the Latin sentire, “to feel”) describes a capacity for feeling, a basic awareness. Many creatures have a basic level of awareness necessary to survive, to distinguish themselves from their environment, find food and avoid harm. Such creatures, particularly vertebrates, are said to be sentient, but in others it is hard to know. All organisms which will survive must respond to their environment and stimuli by way of impulses that elicit changes in position or behaviour, regardless of cognitive function.

This occurs from the cellular level up. A plant moves toward the sun through phototropism driven by the hormone auxin apart from any awareness. Organisms respond to adverse stimuli in what is called nociception, apart from any cognitive ability.

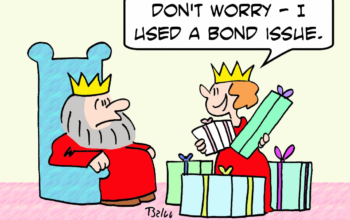

So, the Democrats created a Bill of Rights for Dogs and Cats—and a bill to kill human babies. How sick is it that Democrats want to protect the lives of dogs and cats, yet kill babies—mostly minority babies?

Dogs and cats to get a bill of rights in, yes, you guessed it, California

And why not pigs and parrots, too?

by Randall Otto, Mercornet, 10/6/22

Earlier this year Rep. Miguel Santiago (D-Los Angeles) introduced a bill to the California legislature that would give dogs and cats “the same legal rights and protections the American people have — a formal bill of rights.” Dubbed the “Dog and Cat Bill of Rights,” Assembly Bill 1881 originally recognized:

- the right to be free from exploitation, cruelty, neglect, and abuse.

- the right to a life of comfort, free of fear and anxiety.

- the right to daily mental stimulation and appropriate exercise.

- the right to nutritious food, sanitary water, and shelter in an appropriate and safe environment.

- the right to preventive and therapeutic health care.

- the right to be properly identified through tags, microchips, or other humane means.

- the right to be spayed and neutered to prevent unwanted litters.

While each of these “rights” have, as of April 27, been amended to “deserts,” the bill as amended remains known and cited as the Dog and Cat Bill of Rights. Some of these “rights” (or now, “deserts”) go well beyond “rights and protections the American people have” (what American can claim a “right to a life of comfort, free of fear and anxiety”?), others are simply aspects of responsible care incumbent on human owners (microchipping dogs, e.g.).

The basis for the bill is that “dogs and cats have the right to be respected as sentient beings that experience complex feelings that are common among living animals while being unique to each individual animal.” This is another attempt to attribute rights to animals based on sentiency that is philosophically and practically untenable.

As we argued just over two years ago in Public Discourse when an Argentine judge ordered a chimpanzee released from a zoo on the basis of habeas corpus, human rights must be reserved for human beings.

The criterion of sentience

In 2013, biologist Marc Bekoff issued what he called “A Universal Declaration of Animal Sentience: No Pretending,” in which he defined sentience as “the ability to feel, perceive, or be conscious, or to experience subjectivity.” He drew on the 2012 “Cambridge Declaration on Consciousness,” in which 12 scientists asserted the absence of a neo-cortex does not preclude an organism from experiencing “affective states.” Hence, they concluded, “the weight of evidence indicates that humans are not unique in possessing the neurological substrates that generate consciousness. Non-human animals, including all mammals and birds, and many other creatures, including octopuses, also possess these neurological substrates.”

Advocates of animal rights often equate sentience with consciousness, without distinguishing how consciousness is to be understood.

“Sentience” (from the Latin sentire, “to feel”) describes a capacity for feeling, a basic awareness. Many creatures have a basic level of awareness necessary to survive, to distinguish themselves from their environment, find food and avoid harm. Such creatures, particularly vertebrates, are said to be sentient, but in others it is hard to know. All organisms which will survive must respond to their environment and stimuli by way of impulses that elicit changes in position or behaviour, regardless of cognitive function.

This occurs from the cellular level up. A plant moves toward the sun through phototropism driven by the hormone auxin apart from any awareness. Organisms respond to adverse stimuli in what is called nociception, apart from any cognitive ability.

But consciousness is more than mere awareness—it’s how we experience the world, how subjective experience relates to the objective universe. Consciousness has several dimensions, perhaps contingent on cortical portions of the brain found only in mammals and paralleled in birds.

Fundamentally, primary consciousness and higher-order consciousness must be distinguished. Primary consciousness refers to cognitive awareness of sensory experiences and some internal states, such as emotions. Higher-order consciousness is unique to humans and includes self-awareness, an autobiographical dimension, including episodic memory, the ability to use symbolic expression, such as language and consider truth claims, and a capacity for planning and anticipating the future and self-reflection. Most assertions about the existence of conscious awareness in non-human mammals are concerned with primary consciousness, although some debate the presence of self-awareness in great apes.

Among the numerous logical and scientific fallacies in the Cambridge Declaration is the assumption of a third form of consciousness, affective consciousness, that requires no neo-cortex, with extrapolations beyond scientific evidence and the views of most who work in animal neuroscience, and the bugaboo of animal studies, anthropomorphism.

Most mammals and many non-mammals have an ability to sense, feel and react, while some higher mammals and species of birds have cognition, emotion and the self-regulation enabling them to pursue a goal over the short term; however, higher order consciousness is unique to human beings and requisite to any concept of rights and morality. Dogs and cats have no concept of rights, responsibilities, truth, or morality. They operate on instinct and learn largely through association.

Why just dogs and cats?

If sentience is the basis for animal rights, more animals appear to have a claim than just dogs and cats. One animal rights group cites Bekoff’s article in contending that “the agreed circle of sentience has expanded to include vertebrate animals (creatures with spines), and in particular parrots, dogs, pigs, cows, other farmed animals, and other companion animals. Studies of non-vertebrate animals, including octopus, squid, and cuttlefish, and decapod crustaceans (e.g. shrimp, lobsters, crayfish, and crabs), indicate that they too are probably sentient. Scientists have not yet conclusively determined whether spiders, other insects, and gastropods (e.g. slugs and snails) are sentient.”

If this “circle of sentience” is indeed “agreed,” as animal rights advocates suggest, how it is justifiable to limit rights, or deserts, to dogs and cats? It cannot be because they are the only animals listed that are pets; pigs and parrots are pets, along with “other companion animals.” Virtually any animal a human being keeps as a pet would fall within the parameters of this “agreed circle of sentience” and would appear to have claims for these “rights.”

It seems discriminatory to select only dogs and cats from the “circle of sentience,” a gross injustice.

Granting rights to one species of animal with some “agreed” sense of sentience, such as a dog or cat, and not to another species, particularly among higher primates most closely resembling human beings (orangutans, chimpanzees, bonobos, e.g.), verges on speciesism, which Peter Singer defined (acknowledging Richard Ryder, who coined the idea) as “a prejudice or attitude of bias in favour of the interests of members of one’s own species and against those of other species.”

While human beings alone have the capacity to make such moral determinations and so be “speciesist” (which itself speaks to human uniqueness), humans are those discriminating between animals that could be included within these “rights,” so the accusation may have teeth.

Animal rights advocates generally view all animals as equal. There are no degrees of value. As PETA founder Ingrid Newkirk so inelegantly put it (drawing on the Cambridge Declaration), “a rat is a pig is a dog is a boy.” Standing cannot be based on species membership and certainly not on utility to human beings. All animals should be left to their own wishes, since they know what’s best for themselves.

Practical problems for the bill

If animals should be left to their own ways, they cannot be held in captivity or owned as property. The Argentine judge two years ago ordered a chimpanzee released from captivity in a zoo via habeas corpus, a challenge to the legality of a person’s detention or imprisonment. This was, of course, a legal fiction, since a chimpanzee is not a person having such rights.

It does, however, highlight the contention that animals should not be kept in zoos or as pets, since they are subjects of a life, as philosopher Tom Regan has put it, not objects for human enjoyment. Keeping an animal as property is “animal slavery.”

Hence, the concept of a bill of rights for any animal seems contradictory insofar as they are held in captivity “against their will,” as property. The only real rights that animal liberation seeks is that animals be free to pursue life, liberty, and happiness.

The problem, of course, is that animals have no way of suing for infringement of these “rights.” Advocates must surmise what animals might want based on anthropomorphic assumptions.

Though it may be the case, as bioethicist Jessica Pierce says, “if you give domesticated dogs the choice to be with other dogs—even a sibling—or a human, they’ll almost always choose the human,” that owes to their having been bred to behave unlike what they would have become, which cannot be undone. Rather incongruently, Pierce, along with Bekoff, would have us imagine the lives of dogs in a world without humans. If that is not (yet?) possible, we should at least grant them rights.

Dogs and cats have, in Santiago’s bill, “a right [now, “they deserve”] to be free from exploitation, cruelty, neglect, and abuse.” While each may have anthropomorphized ideas of what that entails, we cannot know if a dog finds it cruel to ask him to beg for his treat or to lie down while we eat our steak dinner. Certainly, making any dog wear an Elizabethan collar, even if we maintain it is for his own good, seems humiliating, if not cruel. Since some animal rights activists consider service dogs “cruel,” what is to become of this great source of help for the disabled?

Dogs and cats are to have “the right to [now, “deserve”] a life of comfort, free of fear and anxiety.” What will be the fate of many working breeds of service dogs, police dogs, military dogs, detection dogs, search and rescue dogs and herding dogs be, given such “rights”? How many humans will die or be at significant disadvantage because these dogs would apparently no longer be able to perform the important services they do.

Dogs and cats are to have “the right to [now, “deserve”] daily mental stimulation and appropriate exercise.” Many children don’t get this, let alone dogs and cats! How would we know what they find “stimulating” mentally? Is rigorous training mentally stimulating or an infringement on their right to comfort and freedom from anxiety? If we have an overweight cat or dog, are we in violation of their right to physical exercise? This “right” or desert doesn’t exist for humans, so how can it for pets?

Dogs and cats are to have “the right [now, “they deserve”] to be spayed and neutered to prevent unwanted litters,” but how would we know if they want a litter or don’t? Most dogs seem to enjoy having puppies almost as much as humans enjoy taking them home from the breeder.

When I last brought home a puppy, I felt the responsibility to ensure he was loved and cared for, since I had unilaterally determined who his new family would be (also true for babies, if adopted).

Conclusion

Some of what are listed here as “rights” or deserts for dogs, cats, and any other animals are projections of what we surmise would be how we would want to be treated, if we were a cat or dog. They are in many ways anthropomorphic projections, as is often true of much else in animal studies.

We cannot really know what our animals want in many instances. To frame these ideas as rights or deserts places them at a level animals cannot comprehend or claim. Only another human being can claim them on their behalf, based on assumptions that may or may not be correct.

The remainder of what are listed as “rights” or deserts for these animals are really aspects of responsible owner care. Animals should have moral consideration, but not rights. We should treat them as our friends and companions, recognizing they are not human beings and so not expecting them to be.

It is because they are not humans and yet lavish us with amazing affection and unwavering companionship that we should seek to live out the wonderful saying, “Let me be the person my dog thinks I am.”